In a word, yes.

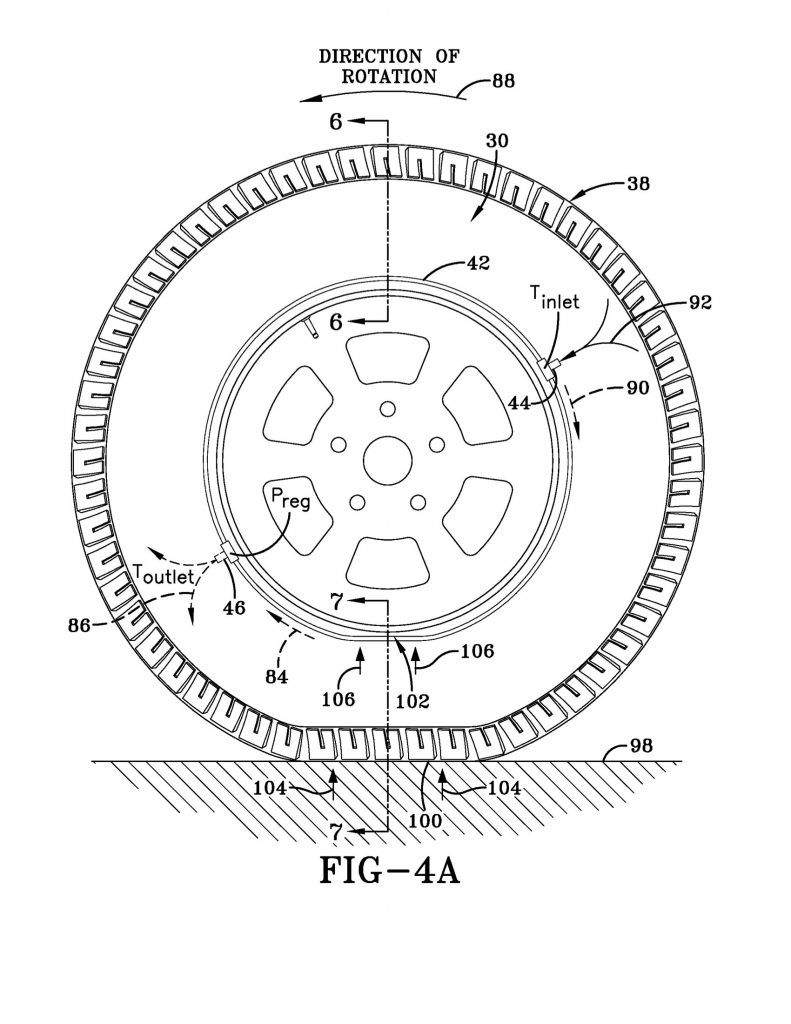

Consider this situation: An entrepreneur comes up with a new invention, let’s say, a self-inflating tire. A big tire company, which has unsuccessfully tried to develop self-inflating tires for years, signs a non-disclosure agreement and comes to inspect the tire. The non-disclosure agreement is a contract by which the big tire company agrees not to disclose what it learns about the self-inflating tire to anyone else and to use the information only to further a business relationship with the entrepreneur.

Relying on the non-disclosure agreement, the entrepreneur shows the big tire company everything there is to know about the invention. The big tire company learns all that it can and secretly photographs the tire. Then the big tire company disappears and does not communicate with the entrepreneur. The entrepreneur believes the big tire company has lost interest.

Three years later, the entrepreneur receives an e-mail from a former employee of the big tire company. The e-mail says:

I am retired now from [big tire company] and see in the news that they have copied your [self-inflating tire]. Unfortunate. I thought China companies were bad.

The entrepreneur learns that the big tire company filed a patent application for his self-inflating tire technology a few months after the inspection and received a patent. One of two named inventors was the person who took the photographs. Over a course of three years, big tire company received eleven more patents for self-inflating tire technology, all of which included technology disclosed by the entrepreneur.*

Yes, this is a real case. The entrepreneur is Frantisek Hrabal and his companies are CODA Development, sro, and CODA Innovations, sro, based in the Czech Republic. The big tire company is Goodyear Tire and Rubber Co. The guy who took the secret photographs was in charge of Goodyear’s self-inflating tire effort. Mr. Hrabal sued to have himself added as inventor and to have the Goodyear employees removed from the first patent, which would effectively transfer ownership of the patent to Mr. Hrabal. Mr. Hrabal also sued for damages under Ohio trade secret law and to have himself added as an inventor for the other eleven patents.

The trial court dismissed the complaint on motion from Goodyear, in circumstances that are ‘troubling’ (the Federal Circuit’s term). The Federal Circuit reversed on multiple errors and sent the case back to the trial court. The Federal Circuit analyzed the law for correcting inventorship of a patent. The relevant statute is 35 USC 256:

Whenever through error a person is named in an issued patent as the inventor or through error an inventor is not named in an issued patent, the Director may, on application of all the parties and assignees, with proof of the facts and such other requirements as may me imposed, issue a certificate correcting such error.

The plain language of the statute provides for correction of inventorship ‘by the Director’ in case of ‘error’ and ‘on application of all the parties and assignees.’ What Mr. Hrabel alleges is fraud and theft, not a mistake. Is fraud and theft an ‘error?’ A Federal judge is not ‘the Director,’ so can a Federal judge issue an order correcting inventorship? Also, where is the ‘application of all the parties and assignees?’ Goodyear certainly has not applied to change the inventors. These questions did not trouble the Federal Circuit.

The Federal Circuit decided that Mr. Hrabel can sue Goodyear to force changes to the named inventors of the self-inflating tire patents. For the first patent, if Mr. Hrabel is ultimately successful, then he and not Goodyear will own the patent.

This litigation is still in the early stages. It remains to be seen whether Mr. Hrabel will successfully prove his case and prevail in the lawsuit, but now he has the chance to try.

The bottom line: If a thief steals and patents your invention, you can sue the thief and have ownership of the patent transferred to you.

*These facts are from the entrepreneur’s complaint, which the Federal Circuit Court of Appeals presumed to be true at this early stage of the litigation. When the case is finally resolved some or all of the recited facts may turn out not to be true.

— R. Yarbrough, Esq.