If you ever doubted the economic importance of branding, take a look at the 2013 World Intellectual Property Report authored by the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO). For the period from 1987 to 2011, United States investments in branding accounted for close to a quarter of all intangible asset investments! Brand ranking organizations value the top 10 brands to be worth between 46 and 91 billion dollars, and between 2008 and 2013, the total value of the top 100 global brands grew by between 19 and 24 percent. Paralleling the enormous rise in value of the top brands is an equivalent “unprecedented” rise in the demand for trademarks.

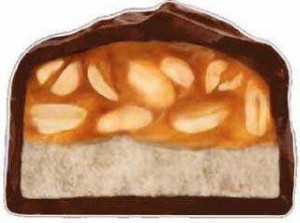

It should come as no surprise then that along with increased competition, brand owners are constantly pushing the envelope in their quest to attract loyal customers. Here’s a great example of a major brand’s recent attempt at expanding its trademark portfolio and the push back it received from a major competitor. Mars, Inc. recently filed a trademark application covering the cross section of its famed Snicker’s bar.

Looking for sweet revenge, the Hershey Company (“Hershey”) opposed the mark on grounds that it is merely descriptive, de jure functional, generic, and fails to function as a trademark. The opposition brief is a lesson on how to disqualify a trademark. Here’s what Hershey says:Mars believes that the cross-section of its candy bar is distinctive enough so when a consumer sees it, he or she immediately thinks “Mars.” How about that for ego? Mars met little resistance by the trademark examiner whose descriptiveness objection was swept aside by Hershey’s contention that the candy bar’s cross-section had acquired distinctiveness over time. The Examiner folded and moved the application on to publication.

- The applied-for mark is descriptive, not distinctive. Candy bars with similar cross-sections are not distinctive but are widespread even among other products: OH HENRY!, BABY RUTH, and PEANUT CHEWS;

- The applied-for mark is generic and not capable of functioning as a trademark;The applied-for mark is “functional because it depicts a candy bar that results from a widely used and comparatively more efficient or less expensive method of manufacture for candy bars containing similar ingredients.”

- The applied-for mark does not indicate the source or origin of the product and, therefore, cannot function as a trademark.

This is a great example of the interaction between aggressive branding, trademark law, and competitive forces. We will follow this story and let you know what happens.

— Adam G. Garson, Esq.