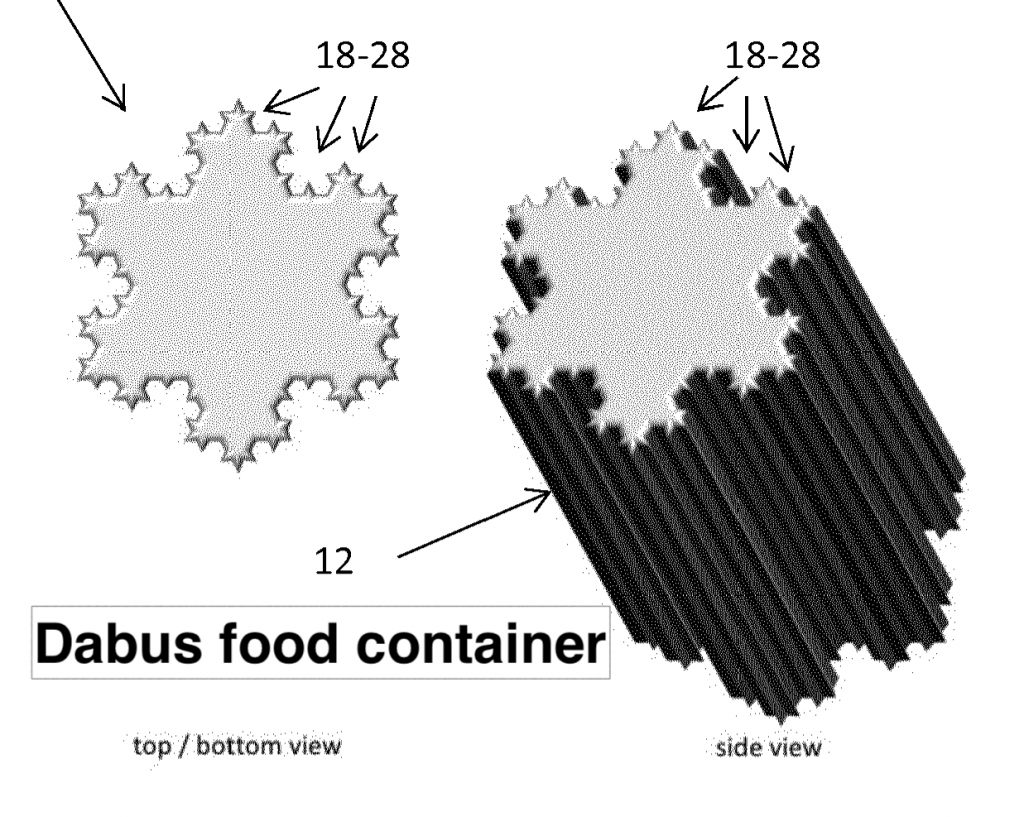

Artificial intelligence (‘AI’) can be pretty smart – smart enough to create new, useful and non-obvious inventions. Take, for example, Dr. Stephen Thaler’s AI tool ‘Device for the Autonomous Bootstrapping of Unified Sentience’ (‘DABUS’). DABUS created two inventions, a light beacon and a food container.

Dr. Thaler applied for patents for those inventions around the world, listing DABUS as the inventor and Dr. Thaler as the invention owner. All of the patent offices to consider the matter have rejected the applications as lacking a human inventor.

Until now.

South Africa has accepted a DABUS patent application and issued a patent, the first country to do so. South Africa has a patent registration system, rather than a patent examination system, so the application was not examined on the merits. Australia rejected a DABUS application for lacking a human inventor, even though ‘inventor’ is not defined by Australian patent law. On appeal, an Australian judge reversed the rejection, holding that a machine could be an inventor. Dr. Thaler is likely to receive an Australian patent listing DABUS as the inventor.

Dr. Thaler had less success in the U.S. and Europe. A U.S. District Court recently upheld USPTO’s rejection based on the use of terms in the statute that indicate that an inventor is human (“whoever,” “himself,” “herself,” “individual,” and “person”). The UK rejected the application because DABUS does not have the capacity to own property and could not transfer patent rights to Dr. Thaler. The European Patent Office rejected the DABUS application because EPO rules require a family name, given name, and a full address for the inventor and that the legislative history required an inventor to be a natural person.

So Dr. Thaler’s results are decidedly mixed, with the major patenting markets rejecting the concept of an AI inventor under current law.

But should patents be issued for AI inventions? Here’s what Dr. Mark Summerfield, an Australian patent attorney, had to say on the matter prior to the decision of the Australian court:

For most of us, the very idea of invention is intrinsically tied to human intellect and creativity. But patent law is not concerned with how an invention comes about. The objective legal test of patentability asks simply whether the invention is something that would not be obvious to a person skilled in the relevant field of technology, in view of everything that is already known and published. A machine does not require human-like intelligence – or, indeed, any kind of intelligence – to satisfy this test. A program that randomly generates combinations of components until it stumbles across something new and useful would suffice. We know that programmers can develop problem solving algorithms (including those employing AI technologies) that perform much better than random guessing. … Automated patent generators capable of monopolizing large areas of technology could become a reality within the decade. Currently, the only legal barrier to this development is the requirement that an inventor be human.

To answer our original question, in Australia and South Africa the owner of the AI tool will be the patent owner. Anywhere else (if the trend continues) there will be no patent to own.

But there’s another shoe to drop. An AI invention tool is merely that – a tool. There’s a human being behind that tool somewhere. Automated systems are used in invention now. To borrow an example from Dr. Thaler, ‘in silico’ screening of drug prospects by pharmaceutical companies uses AI. For patent systems that require a human inventor, and as the participation of machines increases, at what point does the human being’s contribution to the invention process become so slight that the most involved human being is not an ‘inventor’ to qualify for patent protection? We’ll have to wait a bit longer for an answer to that question.

— Robert Yarbrough, Esq.