The patent application process is essentially a negotiation between the patent applicant, represented by his or her patent attorney or patent agent, and the Federal government, represented by the patent examiner. Most communications between the applicant and the examiner are written, in the form of the application itself, office actions by the examiner, and responses and amendments by the applicant.

Sometimes written-only communication works just fine and the applicant and examiner communicate with no problem. Other times, due to the limitations of language, or ability or understanding, one or both of the applicant and the examiner simply do not understand the other, or the application, or the prior art. In addition, the time that the patent examiner can spend on a particular office action is limited by the USPTO’s ‘count system’ of measuring examiner productivity. The ‘count system’ rules patent examiners lives and determines whether the examiner is fired, promoted, or receives a bonus. The examiner simply may not have time to fully understand the invention, or the prior art, or the position that the applicant takes in an office action response. Conversely, the applicant may not understand the reason for a rejection. The opportunity for misunderstanding and miscommunication due to written-only communications is ever-present.

The result can be that the applicant and examiner go round after round until either the examiner allows a patent or the applicant gives up and abandons the application. The downside is that each office action response is both time-consuming and expensive for the applicant.

But the applicant and examiner are not limited to written communications. After the first office action, the applicant has a right to an interview with the examiner, either by telephone, by video conference or in person. Under certain conditions, the applicant can conduct an interview with the examiner before the first office action . The examiner interview is the applicant’s opportunity to negotiate with the examiner in person in real time.

Your loyal correspondent (Robert Yarbrough, Esq.), as a representative of patent applicants, is a great believer in examiner interviews. I believe that examiner interviews really help to correct any misconceptions that the examiner may have about the invention or about the prior art, to allow me to better understand the examiner’s position, and to allow the examiner to meet the inventor(s) so that the examiner regards the inventors as human beings rather than faceless names on a page. At its heart, the interview is a sales tool – I am trying to sell the examiner on the applicant’s position. Anyone with experience in sales knows that an in-person contact is more effective than a pitch on a piece of paper.

My rosy faith in examiner interviews was previously based only on my own experience. Now I have scientific evidence to back up my belief.

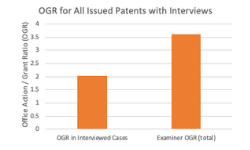

Law professor Shine Sean Tu of the University of West Virginia researched this very point and published a paper entitled ‘Patent examination and examiner interviews’. Professor Tu reviewed more that a million patent applications from 2007 through mid-2020 and compared the results where examiner interviews were conducted and where interviews were not conducted.

The professor’s finding? That where interviews were conducted, on average the patent examiners issued notices of allowance after two office actions. Where examiner interviews were not conducted, Professor Tu found that the same examiners issued notices of allowance after an average of 3.6 office actions. The difference is 1.6 office actions per application. That’s huge, and, on average, the difference between filing an expensive and time-delaying request for continued examination (‘RCE’) and not filing an RCE.

Examiner interviews substantially reduce the number of office actions and responses to get to either an issued patent or an abandoned application. Either way, an examiner interview results in substantially reduced prosecution costs for the patent applicant due to fewer office action responses and substantially reduced prosecution time. Anything that reduces the costs of patenting is a good thing.

By extrapolation from Professor Tu’s results, U.S. inventors are wasting a lot of money by not requesting interviews. How much? Professor Tu reports that the average cost for an office action response is $3,000.00, which comes out to $4,800.00 for 1.6 office action responses. Professor Tu’s study period was 2007-mid 2020. According to the USPTO’s statistics, the USPTO issued 3.3 million patents from 2007 through 2019, which means that about 2.2 million patents were not the subject of an interview. That comes to 3.5 million unnecessary office actions, at a cost of over $10 Billion. That wasted $10 Billion came straight from the pockets of inventors and invention owners. An examiner interview may cost money at the time of the interview, but saves patent applicants money over the course of the application.

Professor Tu did not find that examiner interviews significantly change the results; that is, he did not find that interviews result in more issued patents. Here, my experience and Professor Tu’s diverge. He did not break out telephone interviews from in-person and video interviews. I believe that interviews, particularly in-person and video interviews, definitely help in convincing examiners to allow patents and, in my experience, improve the applicant’s chances of receiving a patent.

— Robert Yarbrough, Esq.