Nearly two years ago we wrote about the Washington Redskins and its efforts to maintain their registration of REDSKINS, which the Trademark Trial and Appeal Board cancelled because it was disparaging of Native Americans. The U.S. Supreme Court took up the cause in an unrelated case, Matal v. Tam, and held that section 2(a) of the Lanham Act violates the free speech clause of the First Amendment because: “It offends a bedrock First Amendment principle: Speech may not be banned on the grounds that it expresses ideas that offend.” The decision was the final word for “disparaging” trademarks but what about “scandalous” trademarks, also prohibited by Section 2(a) of the Lanham Act? At the time we posed the question, the case of In re Brunetti, which dealt directly with that issue, was was working its way through the federal court system.

The facts of the Brunetti case are simple. Erik Brunetti is an artist entrepreneur who founded a clothing line called “FUCT”. According to Brunetti, the clothing brand’s name is pronounced as four letters, one after the other: F-U-C-T. Ah, but one could read it differently, which was the crux of the problem when he tried to register it with U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (“PTO”). The Lanham Act prohibits registration of a trademark that “[c]onsists of or comprises immoral, deceptive, or scandalous matter…” The PTO denied Brunetti a registration and wrote that

Whether one considers [the mark] as a sexual term, or finds that [Brunetti] has used [the mark] in the context of extreme misogyny, nihilism or violence, we have no question but that [the term is] extremely offensive.

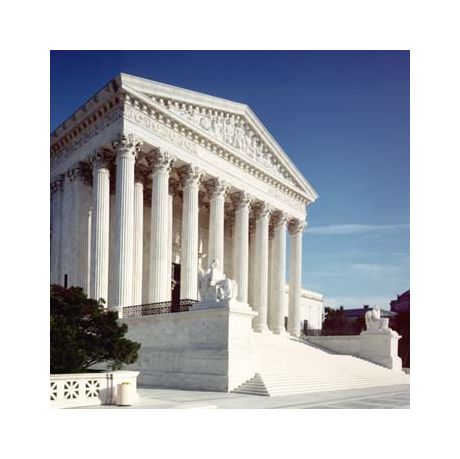

The Federal Circuit Court overturned the PTO’s ruling and now the Supreme Court on June 24, 2019, in an Opinion of the Court by Justice Kagan, affirmed that decision. Kagan wrote that in the Tam case, the Justices agreed on two bedrock principles: “[f]irst, if a trademark registration bar is viewpoint-based, it is unconstitutional. . . And second, the disparagement bar was viewpoint-based.” In other words, viewpoint discrimination doomed the disparagement bar.” Turning to various dictionary definitions of “immoral and scandalous,” Kagan concludes that:

the statute, on its face, distinguishes between two opposed sets of ideas: those aligned with conventional moral standards and those hostile to them; those inducing societal nods of approval and those provoking offense and condemnation.

Historical application of the standard to trademark applications by the PTO, according to Kagan, plainly demonstrates that the “immoral and scandalous” bar is not viewpoint-neutral. For example,

The PTO rejected marks conveying approval of drug use (YOU CAN’T SPELL HEALTHCARE WITHOUT THC for pain-relief medication, MARIJUANA COLA and KO KANE for beverages) because it is scandalous to “inappropriately glamoriz[e]drug abuse.” … But at the same time, the PTO registered marks with such sayings as D.A.R.E. TO RESIST DRUGS AND VIOLENCE and SAY NO TO DRUGS-REALITY IS THE BEST TRIP IN LIFE.

Based on this record and other similar examples, Kagan, asked “How, then, can the Government claim that the “immoral or scandalous” bar is viewpoint-neutral?” She concludes:

the “immoral or scandalous” bar is substantially over broad. There are a great many immoral and scandalous ideas in the world (even more than there are swear words), and the Lanham Act covers them all. It therefore violates the First Amendment.

That concluded the matter. Justices Thomas, Ginsburg, Alito, Gorsuch and Kavanaugh joined. Justice Alito filed a concurring opinion. Justices Roberts and Breyer filed opinions concurring in part and dissenting in part. Justice Sotomayor filed an opinion concurring in part and dissenting in part, in which Justice Breyer joined. If you are interested in alternative reasoning, we recommend reading the other Justices’ opinions.

— Adam G. Garson, Esq.