In 2014, we wrote about copyright litigation involving Mike Tyson’s Maori-inspired facial tattoo. The tattoo artist, Victor Whitmill, sued Warner Brothers Entertainment in an attempt to stop the release of the movie, “The Hangover Part II,” in which one of the characters was tattooed in an identical manner to Mike Tyson. Recall that the wearer of a tattoo has no claims to the copyrights in the design unless he or she has specifically obtained an assignment or license from the artist. More often than not, this does not happen and the artist retains those rights or is free to license them to others – a lesson for tattoo wearers.

The Whitmill case settled. Even though it did not create legal precedent, the copyrightability of tattoos is not in dispute. Tattoos are original works of authorship that are fixed in a tangible medium (skin) of expression. Disputes over copyright ownership, however, continue.

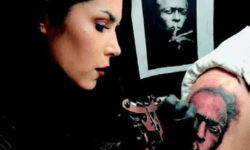

Moving forward a few years, in 2021, Jeffrey Sedlik, an award-winning professional photographer who created an iconic photographic portrait of the world-famous jazz musician Miles Davis, sued Katherine von Drachenberg (“Kat Von D”), a celebrity tattoo artist, for copyright infringement. The suit claimed that she had infringed the copyright of a photograph taken by Sedlik, which she used as a reference for a tattoo worn by Blake Farmer, a lighting technician. Below are the photo and the tattoo side-by-side:

Early in the litigation, the parties filed motions for summary judgment believing that the dispute could be settled as a matter of law. The judge disagreed. While the question of whether Kat Von D illegally copied Sedlik’s photograph is simple, the analysis turns out to be complex. The analysis turns on whether the photograph and tattoo are substantially similar, or whether Kat Von D transformed the original photograph into an image bearing a new expression or message. In the Ninth Circuit, where the lawsuit was filed, federal courts apply the so-called “extrinsic” and “intrinsic” tests to measure the similarity between a work and an alleged infringement. In the extrinsic test, similar features of the works are isolated, and then the court must determine whether they are protected by copyright. In the Sedlik case, the judge weighed the parties’ evidence and concluded that there were sufficient issues of triable fact that could only be determined by a jury. The court arrived at the same opinion with respect to the “intrinsic” analysis, which “requires a more holistic, subjective comparison of the works to determine whether they are substantially similar in ‘total concept in feel’.” The bottom line: the court denied Sedlik’s motion for summary judgment as to copyright infringement.

Kat Von D, in defense of the infringement claim, argued that her copy of Sedlik’s photograph was “fair use.” Here the court analyzed the determinative factors that weigh in favor or not of fair use. These include:

(1) the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes;

(2) the nature of the copyrighted work;

(3) the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; and

(4) the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.

The court explored each of those factors but with an emphasis on the first, the purpose and character of the use. The issues of transformation and commerciality are central to this analysis. A transformative work is one where an appropriation of an original creation leads to a “new creation,” either through changes to the work itself or through placement of the work in “a different context.” Kat Von D argued that the tattoo represents a new expression for three reasons: (1) the tattoo is personal to the wearer, Blake Farmer, and, therefore, presents a new expression of the image and one that must be perceived in context of Farmer’s other tattoos; (2) tattoos create a new expression because they are permanently imprinted on the human body and thus exhibit personal meanings; and (3) Kat Von D used Sedlik’s photo is a reference and added her own interpretation of the image.

The court also looked to whether use of the photograph was of a commercial nature. Defendant argued that it was not commercial because neither Kat Von D nor her employer charged Farmer for the tattoo. Sedlik opposed this argument because defendants “received and enjoyed in direct economic benefit in the form of advertising, promotion and goodwill.”

The judge wrote, “Considering commerciality and transformativeness together, the Court finds triable issues remain as to both elements of the factor, and therefore the first factor cannot be determined as a matter of law.” The court went on to examine the other fair use factors. If you are interested in the details of the arguments raised by the parties, we would urge you to review the court’s order.

In January of this year, the jury returned a verdict for Kat Von D. The trial focused on many of the same issues raised in the summary judgment motions. Arguments were made regarding the substantial similarity and transformative use of the Davis portrait. Kat Von D’s defense highlighted that the tattoo was an artistic interpretation rather than a direct copy, noting alterations in lighting and details that gave the tattoo a different feel and composition from the photograph. Ultimately, the jury decided that Kat Von D’s work did not violate copyright law, emphasizing that her tattoo constituted a transformative use of the original photograph. The New York Times recorded the attorneys’ reactions to the verdict:

“This case should never have been brought,” Alan Grodsky, Kat Von D’s lawyer, said on Friday. “It took the jury two hours to come to the same conclusion that everybody should have come to from the start: That what happened here was not an infringement.”

Sedlik plans to appeal the verdict, his lawyer, Robert Allen, said.

“Obviously, we’re very disappointed,” Allen said. “There are certain issues that never should have gone to the jury. The first, whether the tattoo and the photograph were substantially similar. Not only are they substantially similar, but they’re strikingly similar.”

We have seen no evidence that an appeal was filed. Tattoo artists may rejoice in the verdict but should take heed. With another jury, the verdict could have easily gone the other way. So, if you’re going to copy someone else’s artwork, only a license may protect you from a lawsuit. Otherwise, your livelihood may depend upon somebody else’s (read, judge or jury) determination of “similarity”.

— Adam G. Garson, Esq.