Patent ‘claims’ appear at the end of a patent and determine what is protected by the patent. One purpose of the claims is to inform competitors of what they can do without infringing. Consider the following (entirely bogus) patent claim to an automobile:

An automobile, the automobile having four attractive wheels supporting an optimized frame and a powerful engine attached to the frame wherein the automobile is good-looking, fast and handles well.

Does this claim inform automakers of the limits of what those automakers can and cannot do without infringing the patent? Hardly. This claim is ‘indefinite’ and would not be allowed by a patent examiner or enforced by a court. Actual indefiniteness inquiries are much closer than this extreme example.

Does this claim inform automakers of the limits of what those automakers can and cannot do without infringing the patent? Hardly. This claim is ‘indefinite’ and would not be allowed by a patent examiner or enforced by a court. Actual indefiniteness inquiries are much closer than this extreme example.

But how can we tell whether a patent claim is ‘definite?’ The law says that the patent must have claims “…particularly pointing out and distinctly claiming…” the invention. The U.S. Supreme Court interpreted this phrase in Nautilus v Biosig in 2014. The Court recognized that the limitations of language prevent absolute precision, but:

…we hold that a patent is invalid for indefiniteness if its claims, read in light of the specification delineating the patent, and the prosecution history, fail to inform, with reasonable certainty, those skilled in the art about the scope of the invention.

From the foregoing, whether a claim is indefinite turns on whether an expert in the field of the invention understands the limitations of the claim ‘with reasonable certainty.’

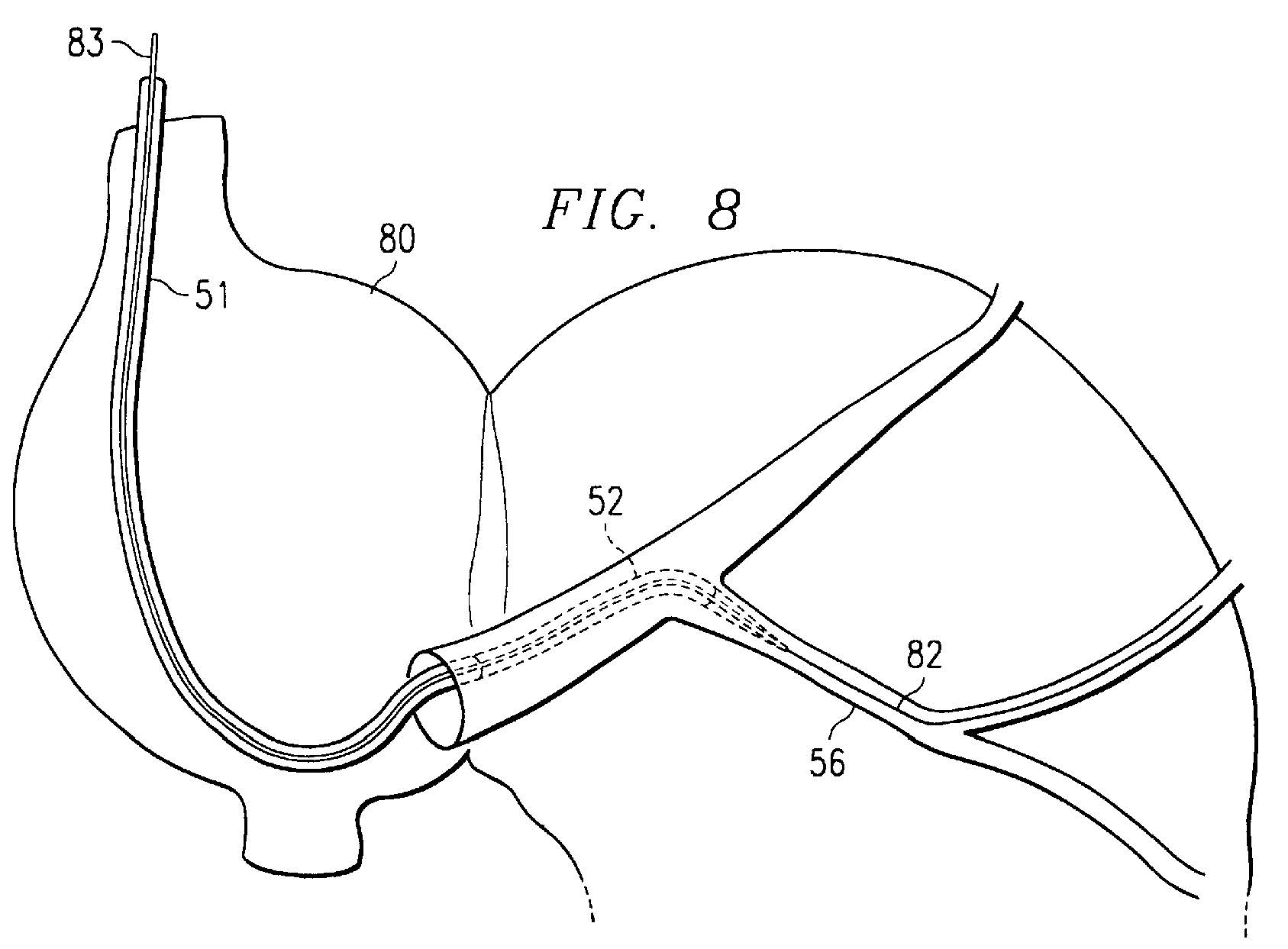

The Federal Circuit recently applied the Supreme Court’s indefiniteness test in Niazi Licensing v St. Jude. Niazi invented a compound surgical catheter to insert electrical leads into the heart of a patient with heart failure. A small, very flexible catheter was fed within a larger, less flexible catheter so the small catheter could pass around tight bends in the veins of the heart. A claim read, in part:

A double catheter, comprising: an outer, resilient catheter…; an inner, pliable catheter… .

Niazi sued St. Jude for infringement, and St. Jude argued that claims were indefinite and hence invalid because of the words ‘resilient’ and ‘pliable.’ The Federal Circuit looked to the patent specification, which disclosed what was meant by ‘resilient’ and ‘pliable,’ including examples of ‘resilient’ and ‘pliable’ materials. The Federal Circuit concluded that the claim language, in light of the specification, was adequately clear so that a knowledgeable person would know what the claim means.

Suddenly, our ridiculous claim to an automobile having attractive wheels, an optimized frame and a powerful motor does not seem so ridiculous, providing those terms are adequately defined by the specification. Why should a patent owner be concerned about indefiniteness? In short, indefiniteness can render you patent claims invalid and unenforceable and waste your money and your time.

— Robert Yarbrough, Esq.