Dear Doc:

I’ve heard the expression, “Fools rush in where Angels fear to tread.” Attributed to Alexander Pope, in An Essay on Criticism, dated 1709. What does this have to do with copyright law?

Signed,

All’s Fair

Dear AF:

In the coming Supreme Court term, the Court has agreed to hear a case which may, at long last, settle the longstanding conflict between “fair use,” which Congress established as a safety valve for deciding when copying is not illegal, and “transformative use,” which some judges have invented as a way to permit what often amounts to outright theft of copyrighted material. How (and even if) the Court resolves this conflict is of great import to both artists and industry.

The case is Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith (“Warhol”), and it arises from a dispute between the successors to Andy Warhol (his foundation) and a photographer, Lynn Goldsmith. It concerns a copyrighted photograph taken by Goldsmith of the late musician Prince, and a series of graphics created by Warhol based on her photo.

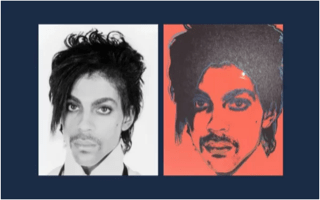

Goldsmith’s original photograph (left) and Warhol’s graphic based on it (right.)

Warhol’s “Prince Series” began with a 1984 limited license agreement from Goldsmith allowing Vanity Fair Magazine to use her Prince photo as an “artist reference.” Vanity Fair commissioned Warhol to create a graphic, for which Goldsmith was paid and credited, but after Prince’s death, the Warhol Foundation licensed Warhol’s graphic (which incorporated Goldsmith’s original photo) to Condé Nast without permission, payment, or credit to Goldsmith for use in its obituary article. Goldsmith objected, and the Foundation sued to obtain a declaration that it neither needed her permission, nor was required to pay or credit her. The Second Circuit Court of Appeals sided with Goldsmith, finding that Warhol’s use was not transformative, and thus, not fair use.

Back in 1976, Congress re-wrote the Copyright Law (17 U.S.C. §101, et seq.) and codified an exception to infringement: Fair Use. Congress said that in order for a use of an otherwise-protected work to escape a finding of infringement, judges should consider four factors: the purpose and character of the use; the nature of the copyrighted work; the amount and substantiality of the portion taken; and the effect of the use upon the potential market. (17 U.S.C. §107). These factors were to be balanced to achieve the goal of the copyright clause of the United States Constitution, “To promote the Progress of Science” (US Const. Art. I, Sec. 8, Cl. 8) (where “science” has its enlightenment meaning — general knowledge).

Soon after 1976, judges started talking about “transformative use” (words that Congress never put into the law) as a way of deciding fair use cases. Since that time, it’s become a sure bet that if you can convince a judge that your use of another person’s copyrighted work is somehow “transformative”, your use will be deemed fair, and you’ll win the case. By most counts, in over 300 such cases, transformative equals fair use over 90% of the time. Transformative use, it seems, has eaten the four factors that Congress intended us (and judges) to consider.

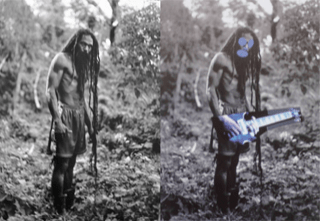

There is just one teeny, tiny problem…judges can’t seem to agree on what “transformative” means, or how to figure that out. Take a photo of an advertisement from an old magazine, enlarge it and sell it for over $1 million? That’s transformative. Take a page from a book of art photographs of Jamaicans and paste an electric guitar onto one fellow’s image? That’s transformative! (Especially if Tom Brady and his supermodel wife Giselle Bündchen pay over $100,000 for it.) (Cariou v. Prince, 714 F.3d 694 (2d Cir. 2013)).

A Patrick Cariou photo (left) and a Richard Prince painting (right) that was found to be a transformative use.

The last time the Supreme Court considered transformative fair use was in 1994’s “Oh, Pretty Woman” case, Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc., 510 U.S. 569 (1994). Only one Justice (Thomas) is still around from that decision. In the past twenty-eight or so years, transformative use has gone from, literally, nowhere to being the single most important consideration that nobody has ever defined. In the important Second Circuit (the appeals court for New York, center of the “art world” in the United States), it often appears that transformative use is like pornography, where the Supreme Court once said, “I know it when I see it.” Stewart, J. In Jacobellis v. Ohio, 378 U.S. 184 (1964).

Now the Supreme Court will wade into the quicksand of transformation, having been asked to define what that means once and for all.

Simply put, the Supreme Court is facing a monumental task now that it has agreed to review the Warhol case, especially because the question presented in the Warhol Foundation’s petition specifically asked the Court to determine the circumstances under which a work of art is “transformative.” Recall that fair use is supposed to be a way of balancing to achieve the Constitutional goal. The Supreme Court has an opportunity to restore some sense of equity to the fair use analysis.

Courts considering transformative use ask whether the defendant has used the plaintiff’s work “in a different manner or for a different purpose than the original.” Some have used the artist’s stated intent (but Richard Prince has flatly denied that he has any intent at all), the viewpoint of a “reasonable observer” or even cast the “court as art critic.” Again, we are at sea. In the Warhol case, the Second Circuit rejected all of these options, stating that judges shouldn’t be in the business of seeking “to ascertain the intent behind or meaning of the works at issue.” Nor, said the court, should the question of whether a work is transformative depend on the “stated or perceived intent of the artist” or the meaning or impression that some critic draws from the work. So much for any semblance of a life raft!

As Harvard law professor Larry Lessig once said, “fair use in America simply means the right to hire a lawyer.” That lawyer can present your case to a judge, but don’t expect a certain outcome…a great many decisions about fair use, by skilled and experienced judges have ended up being reversed by panels of skilled and experienced appellate judges. All of this comes at great expense and greater delay for all involved.

Fair use is a part of the Copyright Law that is encountered by real people on an almost daily basis. Teachers using materials in lessons, users of social media making “memes” and tweeting, artists sampling music, sounds, and images in our “remix” culture all need a better way to determine the boundary of what is fair. The Doc hopes that our Justices are up to the task in ways more effective than what they have done to the law of patentability.

Have a question about whether your use is fair, or any other intellectual property issue? Ask the attorneys at LW&H. They really enjoy this stuff!

Until next month,

The “Doc”

— Lawrence Husick, Esq.